There is a habit many of us have learned without ever choosing it.

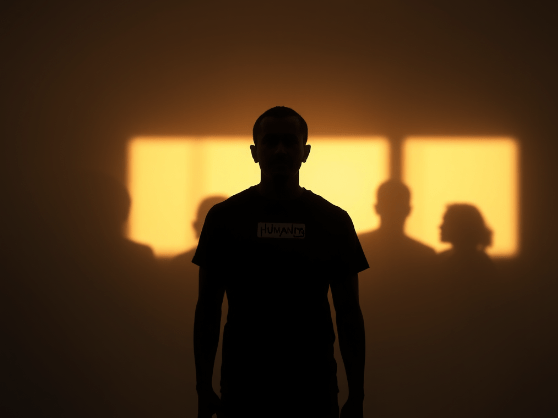

We notice difference quickly. Sometimes before we notice tone. Before mood. Before context. Before story. A label appears and the mind relaxes, as if it has already solved the situation. This person is this. That family is that. Understanding feels complete long before curiosity begins.

Most people do not intend harm when they think this way. The habit is learned, repeated, and quietly rewarded.

Psychology explains part of why this happens. Social identity theory shows that humans naturally organize the world into groups as a way of managing complexity. Henri Tajfel’s research demonstrated that people form in groups and out groups even when distinctions are arbitrary, and once those lines are drawn, perception shifts automatically (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). The brain prefers efficiency, even when efficiency costs accuracy.

The danger is not noticing difference. The danger is leading with it.

When identity becomes the first lens instead of the last, people stop being encountered and start being interpreted. Behavior is no longer something to understand but something to explain away. Over time, expectation replaces observation. The question quietly changes from who is this person to what does this person represent.

Sociology reminds us that this pattern does not develop in isolation. Cultural repetition shapes instinct. Pierre Bourdieu described how repeated social cues form what feels natural, even when those cues are learned rather than inherent (Bourdieu, 1991). When stories, conversations, and public discourse consistently foreground identity categories, the mind absorbs that hierarchy without asking whether it is helpful or true.

This is where exhaustion enters.

Many people feel worn down not because difference exists, but because everything is filtered through difference. Ordinary moments are no longer allowed to be ordinary. Family disagreements become cultural symbols. Public spaces turn into stages. Simple human struggles are reinterpreted as statements. The human scale disappears.

Psychological research shows that fear accelerates this process. Under stress, people rely more heavily on mental shortcuts and stereotypes to regain a sense of control (Fiske & Taylor, 2013). Fear narrows perception. It does not invite understanding. It demands certainty.

Once difference is associated with threat, separation begins to feel reasonable. Exclusion starts to sound practical. Removal feels like resolution. History shows how quickly that logic hardens when it is reinforced rather than challenged.

Scripture warned about this long before modern psychology named it.

In the book of James, believers are cautioned against respect of persons, not because difference is denied, but because judgment becomes corrupted when status or identity leads perception. “My brethren, have not the faith of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Lord of glory, with respect of persons” (James 2:1, KJV). Partiality distorts vision. It replaces discernment with assumption.

Another passage speaks directly to the role of fear. “There is no fear in love; but perfect love casteth out fear: because fear hath torment” (1 John 4:18, KJV). Fear reshapes how people see one another. It creates distance where relationship could have formed. It turns neighbors into risks.

Sociology echoes this wisdom. Gordon Allport’s contact hypothesis demonstrated that meaningful interaction across differences reduces prejudice, but only when people meet as individuals rather than representatives (Allport, 1954). When identity dominates the encounter, the relationship remains abstract. When shared humanity leads, difference becomes context rather than conclusion.

This tension explains why so many people feel trapped between extremes. On one side, calls to ignore difference altogether, which feels dishonest. On the other, constant emphasis on difference, which feels suffocating. Both miss the middle ground where people actually live.

Children learn this ordering early. Not through lectures, but through emphasis. When identity is always named first, they learn that labels come before stories. Over time, that sequence becomes automatic. They are taught to recognize categories before character.

The result is not greater understanding. It is thinner empathy.

Unity does not require sameness. It does not require silence about history. It requires a reordering of attention. Person first. Story second. Context third. Category last.

When societies forget how to tell human stories without leading with labels, they also forget how to see humans without armor. That forgetting rarely announces itself as cruelty. More often it shows up as indifference, suspicion, and the belief that separation is simply how the world must work.

It does not have to.

The smallest corrective is also the hardest. Pause before the label. Stay with the human moment longer than feels efficient. Let curiosity interrupt certainty. That pause is where empathy still lives, even in unsettled times.

References

Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison Wesley.

Bourdieu, P. (1991). Language and symbolic power. Harvard University Press.

Fiske, S. T., & Taylor, S. E. (2013). Social cognition: From brains to culture (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

Holy Bible, King James Version. (1611). James 2:1.

Holy Bible, King James Version. (1611). 1 John 4:18.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks Cole.